was a supermarket in Saluda, SC, and my first regular pay job. It was three doors down from Ben Hazel’s Grocery Store where I used to take lists of items that my mother Leona wanted. Mr. or Mrs. Hazel would find the items and give them to me carry home or arrange for delivery.

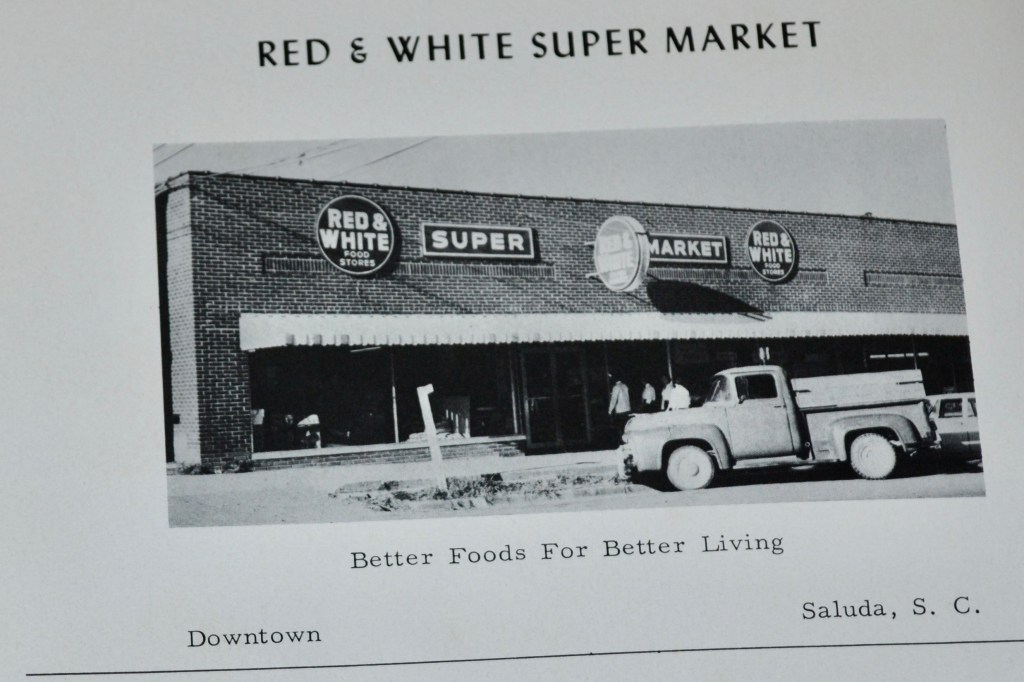

Alfred and Miriam Adams opened their Red and White Supermarket on Church Street just shy of the corner of Main after the Hazel’s Grocery closed. Supermarkets were new and exciting in 1962 when I went to work. I was 14 and at an inflection point in my life because my father died that year.

The Adams were a young couple in their twenties who pooled their savings from working for Winn-Dixie to open their own supermarket when bleach still came in brown glass bottles and frozen food was in its infancy. The store sparkled. All can goods were rotated and faced front. A customer could find his face in the floor. The glass windows were hand waxed weekly by me or Alfred.

I learned how to pack the brown bags that held the items that slid down the counter square. Each item was packed with care. Of course, bag boys like myself carried them to customers’ cars. We usually double-timed back to the store because customers were not allowed to wait and back up. Friendly, fast service was paramount.

I have three university degrees, but in some ways what I learned in that store rivals the substance of any one of those curricula programs. I wore a tie and a white shirt covered by a crisp white apron. My learning was in public and based on following the work of my master, Alfred. He was demanding and taught by showing and doing himself. I watched him work and interact with other employees and customers, imbibing lessons without conscious thought that still stick to me.

Soon I became a good enough stocker to have my own aisles in the middle of store. I stacked cans face forward with speed and efficiency but stopped what I was doing to engage any customer close to me as per Alfred’s way of smiling at each and everyone who entered the store.

Bagging, stocking, hauling empty drink bottles to the back, and unloading trucks led to a promotion to the meat market where I learned how to wrap slice meat, cut chickens, shoulder a side of beef, and grind hamburger. Meat cutters were difficult to find and keep so part of my job was to keep the man in charge happy by making his life a little easier.

George Byrd Yarborough was tall and slim and had curly hair atop his long face. He looked like a movie star with red eyes. Yes, he had the problem; otherwise, he was an outstanding worker who drew customers and kept the most important department in store humming. We sold meat in great volume leading to Alfred employing a young woman in her twenties to help wrap. She was pleasant and sincere but she could not move at super speed or wrap with precision that pleased George. I remember him losing his temper with her and complaining in loud voice from the back about her ineptness to me. In hindsight, I think that was an oblique compliment to me, though I felt sorry for her. Joy was her name. She was soon gone.

Not long after to my great shock so was George. He and his father Horace were killed one weekend over a gamecock. They got into an argument with a handler at cock fight and were gunned down. I did not know much about the incident because it was hushed up but their deaths made the papers as they say. I would no longer be asked to fetch George Byrd’s big two-door DeSoto coupe from the back near quitting time. To this day I see the mint green and white two-tone paint and back seat filled with empty Blue Ribbon beer cans in my head. It was the longest car I had ever driven and shifted via buttons on the left side of the dash.

After a series of temporary meat cutters, we landed Romie Webb. My first impression of him was that the comic book ad for the 90 lb. weakling in need of the free muscle building kit for sale had come to life. He looked like the before image who was suffering sand kicked in his face on the beach with bikini clad beauties looking on.

I was wrong. Romie was strong, efficient, and deliberate. He had an astronaut haircut, fair hair, and black glasses that accentuated his features. As a worker, he was Alfred’s match and that said a lot. He was good with customers but not a talker, which is why Bunk Shealy could so get on his nerves. Mr. Shealy was a retired Ford mechanic who lived nearby with his wife and a great many cats almost under the town water tank. I loved seeing him make his way into our market area holding his cane with his shaky hands. He was there to beg scraps for his cats.

What I most loved was seeing him interact with Romie in a two-or-three-times-a-week showdown. Bunk would start some line of small talk with Romie that was seeded with exaggerations. Romie would play the straight man with a serious demeanor and the kind of questioning voice a lawyer uses in court. Pretty soon Bunk’s scrap bag would be a full as he could manage and the mock hollering contest would conclude. Bunk left smiling and Romie tried to keep his straight face. Their animated theater bit was another part of my Red and White education.

No one from those days looms larger than Luisus (pronounced loo shush) Carrol. He always wore a paper service cap associated with dining establishments and a wide smile. He was singular for being the self-proclaimed best produce man in South Carolina. His friendly bombast was accurate as I found from working in other supermarkets later on. His displays popped; he used colors to break up presentation and displayed fruits and vegetables the way florists work flowers.

In those segregated days he was my only solid link into African-American lives. I had known him in my younger days when he delivered groceries from Hazel’s to our house. His smile and salesman’s skill led to my mother baking an extra pie for him on delivery days. He came into my meat market territory routinely to control the rotisserie that hung over the bacon and sausage portion of the meat counter. I did not take an interest in his barbecue formula but it made the store smell like time to eat. To this day I can still hear his fine baritone singing Down by the Riverside in the back where he readied his merchandise as the doors swung open from the backroom.

My best friend was Nathan Powell who came to reside in the produce department. He learned from the master and soon controlled his area of the store as I did mine when the boss went home. He is the reason I put words down on this site. (See What I Want to Do with danielforrest.org at top.) We used to leave the store as close to 9 P.M. on Saturday night as possible to slide into his old but elegant blue Chrysler for the ride to Winnie Winn’s restaurant. We would find a booth and wait for our hamburger steaks to arrive: two kings of the world on Saturday night. There we were with our stuffed brown pay envelopes in a restaurant ordering food like hot shots and talking about girls and cars. I find tears in my eyes so I want to finish this remembrance with delivering groceries.

Somewhere along the line I became the main delivery van driver which meant keys to the white Chevy van with Red and White logos on the doors and a motor up front beside the driver, no seats in the back. I used it on Wednesdays in advance of double stamp day. The Adams had instigated double Top Value stamps on Thursday grocery purchases. I drove to the shirt plant, hosiery mill, chenille plant, the Nantex, Deering-Milikan: every cotton mill and sewing plant in the textile town of Saluda. I weaved in and out of cars inserting colorful circulas advertising weekly specials under wiper blades of parked cars. The Adams took great care in laying out ads that fetched customers that always included a loss leader like fryers @ 3 lbs. for a dollar.

Driving that van gave me a sense of importance and leads to way to break off my remembering with Saturday deliveries and what I learned from that work. Downtown Saluda was a sea of faces on Saturday with crowds so thick that navigating sidewalks required weaving in and out of pockets of people. The low wall surrounding the courthouse would be covered with sitters engaged in once-a-week-come-to-town conversation.

People would be propped on cars, coming to and fro from stores, and doing Saturday business. We got the groceries to the cars on such days that felt like festivals. Those that did not have a car to be conveyed back home in could count on deliveries. Close to half of our customers were African-American and some did not have driver’s licenses or cars. No problem. You buy groceries with us and we deliver for you.

I made two Saturday runs up and down Bouknight Ferry Road on Saturday to deliver in the solidly segregated area of Saluda. I was a no-nothing white kid popping in and out of homes occupied by people I was not allowed to go to school with or sit in a theater with. Walking in and out of those homes was a trip into a different world.

I remember one order that I sometimes delivered on the far end of Bouknight Ferry by turning down U.S. 378 and driving three miles or so toward Columbia before turning onto dirt lane. I had to coax the lady who rode with me to sit up front in the only other seat in the vehicle. Her children would spread out in back among the bags and boxes of groceries. She felt strange or afraid riding up front with a white boy but it seemed logical to my young mind. I remember the smell of the tar-paper covered shack she lived in. It was nothing like my comfortable house. Flies covered my perspiring face as I lugged groceries in. The canned goods, flour, rice, and sugar I brought in must have seemed like Christmas to it inhabitants. The sink had a pump handle and there were no light fixtures. I saw directly into the heart of racial inequality as I as coming of age and learned lessons that still stick to this day.