Noraly Schoenmaker is a thirty-five-year-old Dutch geologist who quit her regular work to live wherever her dual sport motorcycle is. I watched her ride from the tip of South American to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, and became a fan. She disdains cities and pavement. She rides mainly on dirt. In Season 7 of Itchy Boots (YouTube) Noraly is in northern Africa riding in the Sahara.

Why do I like her vlogs so much? Part of my affection is her relentless upbeat personality, part of it is the places, and part of it is her encounters with regular folks. Last night I saw her sleeping by her out-of-order Honda 300 beside a railroad track in Mauritania in the desolate Sahara. She called Ahmed, a Mauritanian whom she just happened to encounter to help her with a motorcycle problem. Her casual acquaintance was driving seven hours to help her, of course, without a thought, because that is what good people do and the world is full of good people.

I have tent-camped in 47 states and want to think back to some people and places a la Itchy Boots style to remember little scenes that just pop into my head at times. I thought I would start with a Dutchman I met in Virginia.

Loft Mountain

lies along Skyland Drive Parkway in Shenandoah National Park in Virginia and is an extension of the Blue Ridge Parkway. About midway along Skyland Drive (not too far from Washington, DC), Loft Mountain Campground sits on the crest of a mountain with sheer drop-offs and lies across from the biggest natural bald I have ever seen.

I remember the wind making my tent fly like a kite and paying quarters to take a shower but what sticks most is a Dutchman in a decommissioned NATO truck. He was about Noraly’s age and had started his adventure with shipping his camper to Canada and was working his way through the US on the way to Mexico.

Struggling a bit with his Dutch-accented English, I talked to him until someone needed to maneuver around me. He was relaxed and enjoying his voyage through America and was glad to discuss his unusual vehicle, a one-off of his own design. I wish I had gone back as per his invitation to look him up again to understand more about his voyage through North America.

Black Canyon of the Gunnison

is where I met a recently laid off programmer who one of just three campers in April of 2014 when I put my tent down. He caught my eye because he was driving a new silver Chevy Volt. I was in my nearly new Toyota hybrid. We talked cars, weather, and jobs.

He was not all bummed out about his layoff because he had good contacts, was single, and had decided to drive around the country some himself before going back to work. The weather was topic #1: we had a light skiff of snow and a low around zero. I remember using my Coleman stove to heat ice from bottles of water in my trunk that had frozen solid. I had to use my pocket knife to remove the frozen contents in order to turn the ice in coffee.

I suppose the cold is what etched the memory but the beauty of Black Canyon of the Gunnison is striking for its blackness. The rock is closer to pure black than gray and the canyon walls can be traced down to a black river. I learned that one wool blanket and two sleeping bags are not enough; I now take two wool blankets when I camp in high places.

Sam Solomon Springs at Balmorhea Springs State Park

is in the desert of northwestern Texas on the way to El Paso and Ciudad Juarez not many miles off I-10. I lucked into a camping spot via a ranger who respected my tent camping. I could see campers all around as there was little cover and worried a bit about the cluster of fifth wheel campers at the edge of the campground. They were young, sociable and played music loud. A desert party seemed to be forming.

I took off to explore and found signs about the willows that grew freely and the rare fish that thrived in the spring waters and came upon the biggest swimming pool I have ever seen. Like the entire campground, it was a CCC project back in the FDR administration.

The sun was on its way day signaling the sudden shift from intense heat to coldness, but I reckoned I had enough time to avail myself of the product the CCC boys’ toil. I started off attempting laps because the water was cold but soon gave up. Most of the pool was quite deep with a natural bottom. I came back to my tent at sunset and slept well that night because the fifth wheel gang decided to ditch the music for the voices of what seemed like a hundred coyotes in the distance toward Mexico.

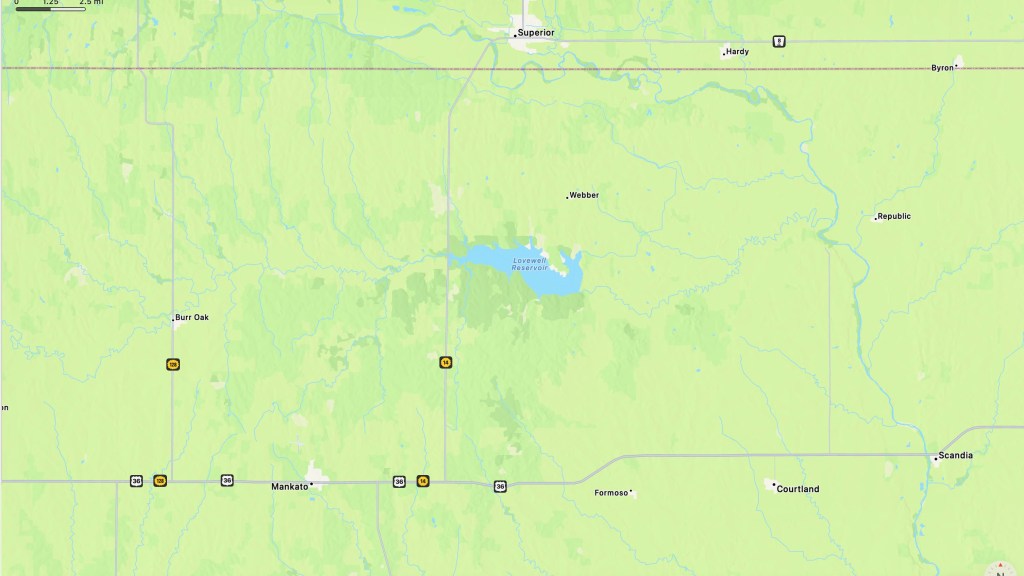

Lovewell State Park at the Kansas-Nebraska Border

is off U.S. 36 in northern Kansas. My hatred of interstates has led me to adopt the route that connects Missouri to Colorado as an alternative to freeway lane-swapping. Because there are no big cities on the route, a driver can go for miles without seeing other vehicles. Small towns crop up every fifty miles or so, untouched by the plethora of national franchises that line the interstates. Most towns look like the fictional Mayberry of Andy Griffith show fame.

I chose Lovewell Lake State Park at 424 miles and 7 1/2 hours driving time from Black Hawk, Colorado, where I had been visiting my daughter Elle and her husband Dave. I was plenty early so I had several hours to read, write, and walk around. I could see a vast storm looking north toward Nebraska about three miles away across the lake.

As I walked around, my Colorado daughter was leaving to visit my wife in South Carolina, but her flight was re-routed well into Canada to escape the storm I was to experience. At the time I did not know the size of the storm which made regional headlines.

I added four stakes to the first four that held my REI tent in place as a precaution. Have I been caught in storms before? Let me count the times. Who cares?

I ducked into my tent around 8 PM to escape the first raindrops and expected, I suppose, a period of rain that would come and go as most East Coast rains do. As soon as I got inside, the wind picked up and vertical rain turned horizontal.

The first half hour was sudden fury that I had never encountered before, but I felt sure that the storm would reach its conclusion and I would survive, wet and unbroken. The second half hour saw my adrenaline-induced bravery turning to fear. The tent threatened to rise like a fat kite. Then it went flat across me and the wet contents of the interior.

I began to think about death during the second hour. The completely sideways rain had soaked nearly every inch of the interior. I became hypothermic. I shivered so much my teeth chattered. My arms ached from grasping the tent frame. Could I hold on?

I longed to release the frame given the lightening but in the puffed up periods I felt holding on was the best of two bad choices. I thought of each member of my family as a way to stay calm and thought how lucky I would feel to have chance to see each again.

Ten minutes short of the two-hour mark, I sensed the storm abating but still as intense as any storm I knew from my east coast existence. I made the choice to inch my way out without letting go of the tent. Standing upright was very difficult. I kneeled on the tent to remove some of the stakes and fly.

My equipment remained on the ground long enough for me to get to the car. My new fear was that the car door hinges would bend open too much so I kept them closed but managed to pop the trunk open.

I began to feel I could control my shivering as I worked up a little heat from my wet work. I got the now extraordinarily heavy tent and its contents in the trunk. The wind had diminished and the sideways–always sideways–rain was just drizzle now.

Shifting to the far side of the car, I found some dry clothes and a towel and got myself into the vehicle at last in a wind that still threatened to topple me. I cranked up the car and sat for a few minutes before heading out.

My Rand McNally Road Atlas and the Toyota navigation screen showed U.S. 36 tantalizing close. I decided to head east and then cut back south to it. My drive in was a good ten miles back west on a very poor remnant of a paved road.

What I noticed first was my sleek sedan was somehow going sideways south though I was moving forward. Seemed illogical. I drove on and came to an intersection that would allow me to proceed to good old paved U.S. 36 but drove on until I found yet another intersection of dirt roads that promised a shorter trek to pavement.

I had not reckoned on was what I could hear: mud caked up in layers in the fender wells that slowed the wheels down. I had determined to drive steadily without stopping to reach the bottom of the long hill that was no doubt part of the geographical dip that had allowed Lovewell Lake to form.

A hundred yards are so down the dirt road so tantalizing close to pavement, my sedan stopped going forward. I checked my watch and the clock and spoke aloud: “I can spend the rest of the night right here and walk back to the campground at daybreak.” It was already after 2 AM.

I did not sleep to speak of but took some comfort in the fact that I heard dogs barking in the distance. Everything would be ok in the morning. At around 4:30 AM I got out of the car. I struggled to keep my sandals on as I inspected my clogged wheel wells. Using a stick, I worked for a quarter of an hour or more to remove soil that seemed like ground rock on its way to becoming dirt.

I scouted the road backwards and forwards as best as possible for a few yards north and south. I decided to back up north toward Nebraska because I knew that the road I had turned off of was on higher ground. To my surprise the traction control and reverse worked on the gummy soil that was beginning to dry.

I drove back toward the campground and turned right toward what led to Webber, Kansas. Webber has a name but it is not a town, just three or four buildings, tops. I drove north some more and then turned east drove for the best part of an hour before I found a paved highway inside Nebraska that I could have gotten out and kissed.

Storms in rural Kansas and Nebraska have a width, breadth, and duration that those on the east coast lack. The scale of that storm is something I still struggle to understand.

Antelope Island State Park

is very close to Salt Lake City, Utah, on a long island in the middle of lake which is likely to disappear soon due to a draught and over-irrigation.

Once I toted my gear in and set up camp, I made a series of short hikes: the first to swim in the lake. I was an absolute excellent floater for the first time in my swimming life.

What amazed me most was being so close to a major city yet remote from it with sight lines to mountains twenty miles away. Toward sunset I followed well-dressed “hikers” moving up to a trail to a high point.

I spoke to some of the guests and did what they were doing: I photographed the beginning of the newly weds’ married life.

I remember the hiking and swimming and the vastness. Vastness is hard to come by on the east coast.