I grew up mainly at 513 West Church Street where downtown ends and gives way to the McCormick Highway three blocks from the beginning of the heart of Saluda. One of the three children of Harold and Leona Forrest, I was ushered outside at every turn, though I was not one stay inside. To this day, I feel better outside than inside.

I can still mentally walk through spaces I once inhabited. I have never seen an episode of The Andy Griffith show that did not kick up Saluda memory dust. Places attach to my mind more than people. Why is the Saluda of my boyhood so present in mind?

My age, I suppose. Nostalgia grips my melancholy soul from time to time. The loss of an age is another possibility. On my zig-zagging tours of the United States to visit National Parks and historic sites, I have come to prize the small towns that still seem close to vibrant. The age of the electronic screen and ordering on line has sapped the vigor from towns and I yearn to see them still thriving.

I found my tent camping spots mainly via two-lane, non-interstate highways to stare at countryside and small towns. They are still out there but most are ghosts of themselves. Pick a state. Most of its citizens are clustered in a handful of key cities surrounded by suburbs. Relatively few of us live in the type of space idealized on The Andy Griffith Show and in my mind.

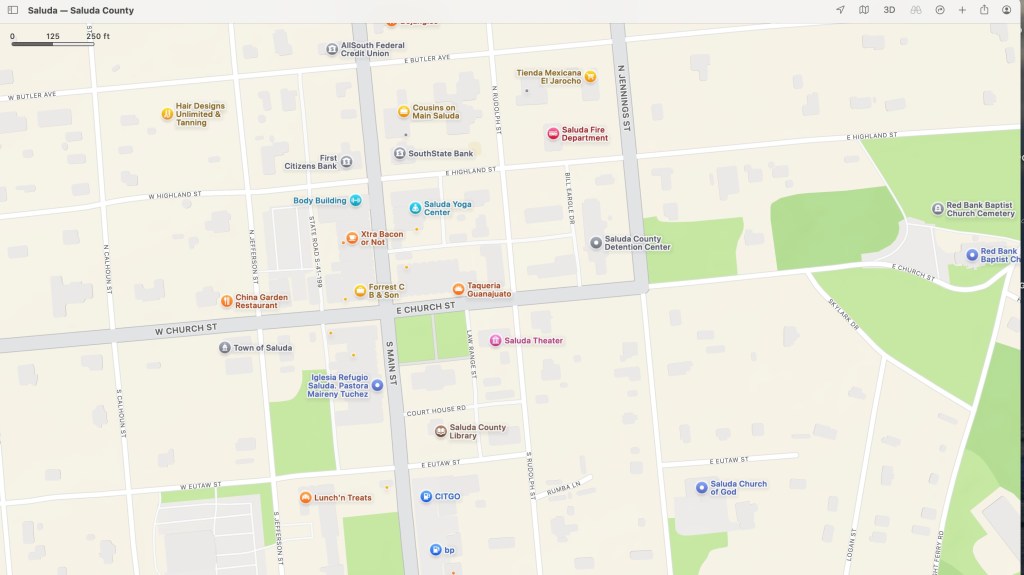

At ten or so were I on the sidewalk above, I would be in site of the post office across the street on the right and in front of the old Red Bank Baptist parsonage. I was friends with Reverend Thomas’s son Mike and I remember his house as I do all of those along the way. In most cases I knew the inhabitants personally. I could be on an important errand and I loved important errands at ten. My mother would give me a dollar and bid me bring two packs of Viceroy cigarettes home.

Just beyond the trees is the site of Preacher Bryant’s corner gas station. Preacher was always glad to help me. I liked the looks of his shiny black hair slicked back with waves on the side. “Why was he Preacher?” I wondered to myself. He readily bought all the three-cent returnable soft drink bottles I found on bicycle rides on my Western Flyer by searching the ditches along side the McCormick Highway. Of course, I gave most of the earnings back to him for a soda pop and candy bar.

I felt secure somehow in knowing that Preacher knew me, Harold’s boy. I don’t know anyone now who runs a gas station but I knew the proprietors of the town’s four or five gas stations. The corner of Preacher’s Shell Station was where J.W. Adams 1958 aqua and white Corvette burned and melted down to the frame and motor block. I still remember the fierce black plume of smoke that hung in the air and weird new-to-me smell of plastic/fiber glass burning that drew me to the improbable sight of a melted car.

The brick building across the street was the post office and next to it was Henry’s Cleaners and a washeteria. I was often in and out of the post office on errands. I loved looking back into the work area where postal employees would put letters in the line of rental boxes.

The Saluda police chief and jail were opposite of the post office. I doubt that I ever passed without checking for cop car, of keen interest to a small boy.

Duffy’s Cafe sat on the corner across from Preacher’s facing W. Church and N. Jefferson. Cars usually lined the N.Jefferson side. My youth was pre-interstate and travelers on the way to and from Atlanta pulled in under the green and white awning to eat a restaurant that offered booths and counter seats attended by uniformed waitresses. Did I ever eat there?

Not sure but I ate next door at Frank Hite’s double door grill when I was older and working at the downtown Red and White. The right-hand door was for African-Americans only. I wish I had the nerve to do what I wanted to: go into the right-side.

I was sometimes forced to eat at the counter, but it had the advantage of being able to watch Mr. Hite, cigar in mouth and Merita bread service cap on head, press the grease out of the burgers he was about to serve. Me, I was a chili dog man and preferred the tables that lined the walls because I could fiddle with juke box playlists that were wired into the big machine. I loved listening to Ray Charles and Johnny Mathis in those left-handed side Jim Crow days. Seemed so ironic. Looking back, I think Mr. Frank must have been brave to run an establishment that allowed African-Americans to eat buy food in the shrunk right-hand side stand up portion of his establishment.

Across W. Church from Hite’s was Mathews Chevrolet, my favorite place when the new cars started arriving. The late 1950s and 60s was a time when automakers innovated by changing sheet metal in odd ways and decorating their creations with two-paint jobs and plenty of chrome. I remember walking down the alley by Mathews to look at the half a dozen or so new models that were still covered waiting their fall introduction date. Exciting times for car crazy kid.

Crossing back over W. Church would place me in front of a building that housed Ben Hazel’s Grocery Store. The Hazels ran the boarding house that I passed on my way to town which may have come after they closed their store. Groceries stacked impossibly high caught the eye upon entering. One of the Hazels would take the customer’s order and pull the items from the shelves which sometimes required a sliding ladder to reach. It is the only pre-self service grocery store that I remember as a small boy. I think that my mother Leona mainly handed over a list that would result in the order being delivered by Lucious Carrol later in the day after I dropped it off.

The next building had an elaborate set of steps in front of it and once served as a skating rink. Beside it ran an alley street next to the Red and White, a downtown supermarket with plate glass windows that had the weekly specials affixed.

The old Red and White used to be Ruff’s Red and White before a young couple, Miriam and Alfred Adams, bought it. I was 13 when I went to work for them and remained in their employ until I left Saluda in 1967. I have memories of sorting soft drink bottles in the back near the frozen food storage and busting out a mop to clean up broken brown glass Clorox bottles.

Just beyond it was another most familiar place next to C.B. Forrest and Sons: the barber shop where Truman Trotter (my favorite) and Oscar Forrest cut hair. What a privilege it was to sit and look at hunting and fishing magazines while three or four grown men sat and talked while having their ears lowered. My favorite cut was the astronaut look, a crew cut achieved by using a wide metal comb across the head and a pink concoction called Butch Wax.

Across the W. Church Street from these building was the Christian Science reading room, which I never understood, and the bank. I can remember going into the bank on my lunch break from the Red and White and using $750 of my accumulated money in December my junior year to buy a used 1965 Mustang in 1966 for $1200. I was so proud, so nervous. My mentor Alfred Adams had talked me out of buying a beat up Falcon convertible for $600 cash and going for the newer car. Likely Mr. Adams spoke to Holmes Hurt who ran the used car lot. Alfred Adams was a bit of a car buff himself and soon traded his beautiful SS Impala for a 1966 Mustang.

The side door of C.B. Forrest and Sons next to outside mural was suddenly locked one Saturday when I was inside just beyond the Adam hat rack by the men’s suit section making up suit boxes to fill the cavities on both sides of the three-part mirror that I loved looking at myself in. “Am I the person I see?” I thought to myself.

A man dressed in D.C overalls who had been trying on hats had fallen to the floor backwards. Mrs. Edwards, a clerk, fetched my dad who ordered the door locked and went across and up the street to get the police. One of the man’s hands was grazing the sports section and pushing back against the colorful fabric of bright blazers. After seeing my first dead man (heart attack I presume) I was sent home via one of the two front doors.

This 2007 shows Alan Harmon and my first cousin Brad Forrest just outside the side door. I have many memories that come alive when I enter that space. Because it is on the corner of Church and Main Streets and faces both, it is still one of the best known landmarks.

Turning left just past the side door would lead me to one of my favorite places from the Saluda in my mind. Three store fronts up Main St. back then just past the Piggly Wiggly and the insurance agency that so graciously helped my boyhood self navigate car insurance is a building that housed the jewelry store. Mr. James Pough or Mr. Hubert Humphries helped me pick gifts for my mother and more importantly watches, radios, and rings. I remember purchasing more than one friendship ring which I sought to bestow on one girl or another.

The proprietors like all those in the stores I frequented were proof of the African proverb that Hillary Clinton used in her Presidential campaign: it takes a village to raise a child. Unbeknownst to me I was being guided into adulthood.

Across Main Street from the jewelry store sat store #1, hands down: the F & S Drugstore. Sure I went in there to get Dr. John to fill prescriptions for my mother and I enjoyed a cherry soda now and again made by Mrs. Francis Rankin, but I came in for the comics. Just inside the door to the right was the You Tube of the era for my young self: a magazine section with a generous comic selection. My brothers and I shared a bedroom and a closet. I tried to keep my stack of comics separate and neat and was more than a little cross if Cally or Butch borrowed without notification.

Nextdoor to the F & S was Shealy’s Barber Shop and then the library I knew as a boy and next to it on the right was a small attached hut that served as snow-jo stand in hot weather. Some of my downtown destinations had something brand new and not part of homes yet: air conditioning. I loved chances to visit penguin territory.

I am mentally walking back toward the red light intersection of Main and Church now astride what used to be Luke’s Apparel. I often took a sharp left there to find myself across the street from the Saluda County Courthouse. Just past Luke’s was the clothing spot to visit for sure: Simon and Henrietta Wolfe’s store.

My friend Johnny Wheeler and I used to take our narrow brown pay envelopes with the $20 or so of our Red & White earnings into the store after the market closed at about 7:30 P.M. on Saturdays. The Wolfes had a good eye for what young men wanted to wear. I remember Jantzen sweaters and Gold Cup socks.

Across W. Church which had become E. Church on its way down to Red Bank Baptist Church stood the court house which was in front of one of my favorite shopping destinations: the Stuarts’ Western Auto Store. I shopped baseball gloves there and could count on a clerk named DeWitt to help me with my bicycle. Beyond it on the same side was a cafe and Bank’s Supermarket.

Just past Bank’s along N. Rudolph St. was the segregated world that Jim Crow had imposed which picked up and again on Boughtknight Ferry Road. African-Americans were part of a separate world back then with their own business and dwelling zones. Only in my high school years did I begin to understand the separate and terribly unequal system when I adopted Martin Luther King as my hero.

Crossing the E. Church near Bank’s and heading back toward the court house led to a one-way lane in front of the Indian Chief Theater. It drew me to town in my younger days almost every Saturday for a double-feature.

My daughter Danielle (Elle) stands in front in this 2015 photo. She has some vague idea of my childhood Saluda but her theaters and stores were in malls.

Mentally I am now back to my free-range ten-year-old self at the corner of Main and Church in front of the courthouse with a view of what used to Wolfe’s and C.B.Forrest and Sons at the one and only red-light. The photo shows the corner with the bank on the far left.

Time to cross Main in front of the bank and take a left toward where the roads lead to Ridge Spring, Johnston, and Batesburg. I had some interest in Pitts Drug store where I won a date with a pretty girl who worked there but my big stop was farther down the street past the flower shop to B.C. Moores. I think it was part of a small chain of clothing stores and back in my early teen years I would go inside to peruse the latest shirt fashions.

The core of the town of Saluda dropped away at W. Eutaw Street at the stand-alone diary stand in the vacant lot across from what is now the Saluda Library. I would turn west on Eutaw to walk home past Davis Tire where I later bought recapped tires and the site of the old Saluda School–later the new Piggly Wiggly–where I began my academic life. I walked shady streets on my way back home, unless I peeled off to find myself hanging out with the myriad young kids in post-WW II Saluda who were growing up in our Mayberry.

In high school I secretly wanted to be a farmer, not a town kid. My friends Gehrig Minick, Randy Robertson, David Hallman, Morris Jones, Jones Butler, etc. were a cool crew in their blue corduroy Future Farmers of America jackets. I longed to be a farmer’s son, but my town life was a rich experience that taught me in the way life in the country teaches its young through agriculture.

The kind of tight-knit village life I knew then is gone– outside of dense city neighborhoods that can be found in places like Brooklyn. Most of us live sterile suburban lives more alone than joined. I was a privileged youth of Saluda at its height in the 1950s and 1960s.

Most of this walk through Saluda can probably be laid to nostalgia for youth period, which brings me to a few lines from Dylan Thomas’s Fern Hill, an eloquent statement about youth from the remembered point of view of a rural youth.

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honored among the wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daises and barley

Down the rivers of windfall light.

And as I was green and carefree . . .